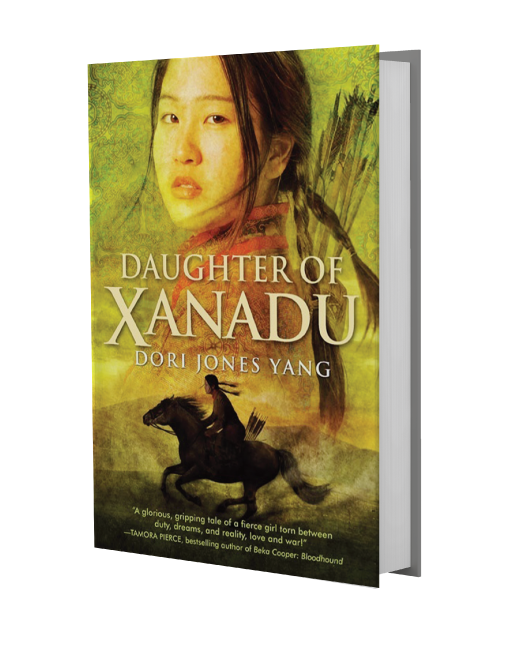

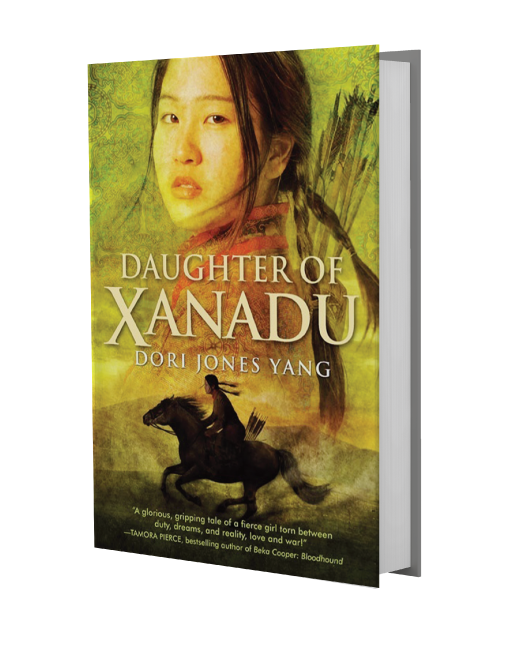

“A glorious, gripping tale of a fierce girl torn between duty, dreams, and reality, love and war!”

—Tamora Pierce, bestselling author of young adult fantasy books, including Song of the Lionness Quartet

Daughter of Xanadu

Daughter of Xanadu, published by Random House/Delacorte Press in 2011, is a historical novel about a daring 16-year-old named Emmajin, imaginary granddaughter of Khubilai Khan. Emmajin wants to join the Mongol Army and become a legend on the battlefield; her plans get complicated when she meets a charming foreigner from a distant land – named Marco Polo.

AWARDS

The Amelia Bloomer Book List, American Library Association, 2012 selection.

“Outstanding Merit,” Bank Street College of Education Best Books of the Year, historical fiction, 2012.

National Council for the Social Studies, Notable Trade Books for Young People, world history and culture, 2012.

A love story set in 13th century China…

Athletic and strong willed, bold and beautiful, Princess Emmajin is determined to do what no woman has done before: become a warrior in the army of her grandfather, the Great Khan Khubilai. In the Mongol world the only way to achieve respect is to show bravery and win glory on the battlefield. The last thing she wants is the distraction of the foreigner Marco Polo, who challenges her beliefs in the gardens of Xanadu.

Marco has no skills in the “manly arts” of the Mongols: horse racing, archery, and wrestling. Still, he charms the Khan with his wit and story-telling. Emmajin sees a different Marco as they travel across 13th-century China, hunting “dragons” and fighting elephant-back warriors. Now she faces a different battle as she struggles with her attraction towards Marco and her incredible goal of winning fame as a soldier.

Read a Short Excerpt

I showed Marco Polo where to stand, at a precise distance from the target, next to me. He hesitated, then stepped into place. He was so close I could feel the air vibrating between us like a newly released bowstring.

“You hold it like this.” I demonstrated with my bow. “Then pull back, aiming up. Then bring the bow straight down, like so.” I shot an arrow that hit the target but not perfectly. Marco’s closeness had again distracted me. The soldiers who acted as judges gathered around the target and showed with their hands how far my shot was from the center.

I handed Marco my bow. “Try.”

Marco caught my eyes with a slight frown, as if saying, Why are you torturing me? But he turned to the soldiers watching him. “My friends, I am a merchant, not a soldier.” In a friendly way, they urged him on.

Finally, he took my bow and fitted the arrow onto it.

Connecting generations and cultures through the lives of ordinary people

Dori Jones Yang is a writer who aims to build bridges between cultures and between generations. Author of a wide variety of books for different audiences, she loves to explore different countries, explain complex issues in understandable language, and make history come alive.

Dori Jones Yang

Author Comments

Marco Polo appeals to me because he was the first person from the West to write about China. Yet many of his readers back home were skeptical; they did not believe him when he described the wealth and wonders he had seen. As a U.S. foreign correspondent, I spent many years writing about China, and I found that my readers, like Marco Polo’s, didn’t understand or “get” a lot of what I observed in China. Like Marco, I tried to build a bridge between East and West, enhancing understanding.

My husband first suggested I write about Marco Polo. But Marco Polo’s viewpoint, the white male perspective on history, is one we Americans already find familiar. So I decided to turn history on its head, to tell the story as seen through the eyes of an Asian woman. I tried to imagine: What did Marco Polo look like to her? What did she think when he described his homeland, Europe, to her? How did their values differ? How did she change when exposed to his perspective? And how did he change, after meeting her?

Europeans and Americans traditionally have viewed the Mongols as barbarian invaders. That is the way the Russians and Poles and Hungarians experienced them in the 13th century. But to Mongolians, those Mongol hordes under Genghis Khan were heroes, brave soldiers with brilliant military tactics, able to outsmart and outfight armies from nations far bigger and more literate. History looks different if it is told by the victors or the vanquished.

I traveled a lot to research this book: to China, to Mongolia, to the Silk Road. In Khanbalik, now known as Beijing, I found segments of the old Mongol city wall. In Carajan, now called Yunnan, I visited three pagodas that were there when Marco Polo visited. I walked through a Buddhist monastery built on the site of Karakorum, the first capital of the Mongol Empire. I found a memorial built to Genghis Khan, where worshippers burn incense to honor him. And I found, most amazing of all, the ruins of Xanadu, the summer palace of Khubilai Khan, in the grasslands of Inner Mongolia, north of Beijing. All that remains of that glorious palace and gardens are crumbling stone walls and meadows of wildflowers; but Xanadu was real.

Author’s Comments

Marco Polo appeals to me because he was the first person from the West to write about China. Yet many of his readers back home were skeptical; they did not believe him when he described the wealth and wonders he had seen. As a U.S. foreign correspondent, I spent many years writing about China, and I found that my readers, like Marco Polo’s, didn’t understand or “get” a lot of what I observed in China. Like Marco, I tried to build a bridge between East and West, enhancing understanding.

My husband first suggested I write about Marco Polo. But Marco Polo’s viewpoint, the white male perspective on history, is one we Americans already find familiar. So I decided to turn history on its head, to tell the story as seen through the eyes of an Asian woman. I tried to imagine: What did Marco Polo look like to her? What did she think when he described his homeland, Europe, to her? How did their values differ? How did she change when exposed to his perspective? And how did he change, after meeting her?

Europeans and Americans traditionally have viewed the Mongols as barbarian invaders. That is the way the Russians and Poles and Hungarians experienced them in the 13th century. But to Mongolians, those Mongol hordes under Genghis Khan were heroes, brave soldiers with brilliant military tactics, able to outsmart and outfight armies from nations far bigger and more literate. History looks different if it is told by the victors or the vanquished.

I traveled a lot to research this book: to China, to Mongolia, to the Silk Road. In Khanbalik, now known as Beijing, I found segments of the old Mongol city wall. In Carajan, now called Yunnan, I visited three pagodas that were there when Marco Polo visited. I walked through a Buddhist monastery built on the site of Karakorum, the first capital of the Mongol Empire. I found a memorial built to Genghis Khan, where worshippers burn incense to honor him. And I found, most amazing of all, the ruins of Xanadu, the summer palace of Khubilai Khan, in the grasslands of Inner Mongolia, north of Beijing. All that remains of that glorious palace and gardens are crumbling stone walls and meadows of wildflowers; but Xanadu was real.