“This book reveals a generation of Chinese Americans that has long been overlooked by historians. These stories of the lives of some of Seattle’s leading citizens will fascinate and delight.”

—Gary Locke, Former Governor of the State of Washington

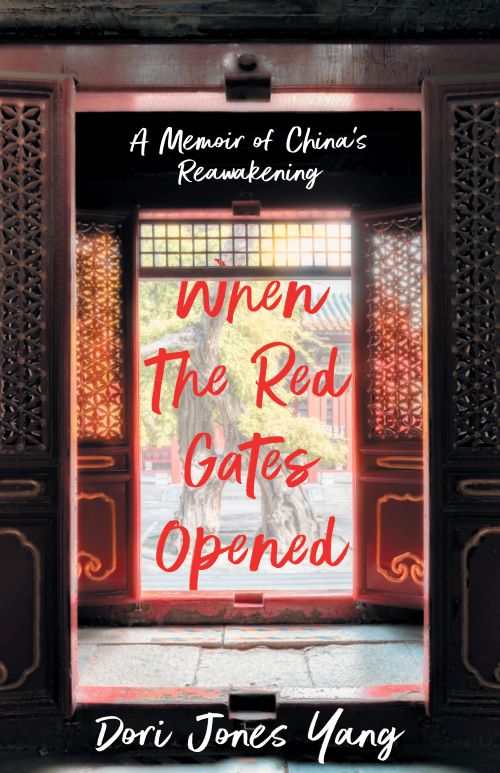

Voices of the Second Wave:

Chinese Americans in Seattle

Many Americans know about the “first wave” of Chinese immigrants, who worked on the railroads, mined for gold, and built Chinatowns. Less known is the “second wave” — most of whom came to the U.S. as students in the 1950s and 1960s, spoke Mandarin, and earned advanced degrees. Although most found professional jobs, they were cut off from their native country and worried about relatives left behind after the revolution. This ground-breaking book collects the bittersweet stories of 35 people from this “second wave” generation of Chinese Americans, who tell about their lives in their own voices.

In honor of a generation of Chinese Americans…

Dori Jones Yang conducted more than 35 interviews for this book as a way of honoring this generation of Chinese Americans. She then edited and polished the transcripts, using the interviewees’ own words to tell their life stories.

These stories reflect the lives of many of the “lost generation” of Chinese immigrants, who were cut off from the land of their birth. All those featured in this book were born before 1949, so their childhood memories include the turbulent years of the Japanese occupation, the Chinese civil war, and the flight of millions from mainland China because of Communism. Immigrants from this generation settled in all parts of the United States, so every major American city has such Mandarin-speaking communities. Those interviewed for this book lived much of their lives in the Seattle area, but their experiences are typical of their generation across the United States.

Read a Short Excerpt

In the mid-1800s, the “first wave” of Chinese immigrants began to come to the United States to search for gold. As time went on, they built railroads, created Chinatowns, and worked in low-wage jobs in laundries, at restaurants, on farms, and in factories. . .

The “second wave” of Chinese immigrants differed markedly from that first wave, and much less has been written about them. After the Japanese invasion of China, and especially after the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in 1949, many young Chinese students came to the United States seeking an education. Men and women, they came from all parts of China and spoke Mandarin, the language of higher education throughout China, as well as their regional dialects. . .

This group of young people included many of China’s “best and brightest,” graduates of China’s top universities, sons and daughters of its entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, and government leaders. Most came to the United States for graduate school, and many studied science or engineering, the academic fields most valued back home in China. Their education and skills were badly needed in their homeland, and normally, most would have returned home to help modernize China.

They became a “lost generation.” Most were cut off from the land of their birth for many decades.

Connecting generations and cultures through the lives of ordinary people

Dori Jones Yang is a writer who aims to build bridges between cultures and between generations. Author of a wide variety of books for different audiences, she loves to explore different countries, explain complex issues in understandable language, and make history come alive.

Dori Jones Yang

Author Comments

This book was definitely a project of the heart. Maria Koh, who commissioned me to write this book, wanted to ensure that this aging generation of Chinese American immigrants would have a chance to tell their stories. My husband, Paul Yang, is typical of this generation: His family fled from Shanghai to Taiwan in 1949, and he came to the United States in 1962 for graduate school and stayed to work as a city planner for many years.

I found it fascinating to use my reporting skills to elicit stories from thirty-five people with similar backgrounds yet very different immigrant experiences. I was delighted when the Library of Congress asked me to speak on this topic and requested the audio recordings and full-length transcripts for its collection, now available for future researchers.

Author’s Comments

This book was definitely a project of the heart. Maria Koh, who commissioned me to write this book, wanted to ensure that this aging generation of Chinese American immigrants would have a chance to tell their stories. My husband, Paul Yang, is typical of this generation: His family fled from Shanghai to Taiwan in 1949, and he came to the United States in 1962 for graduate school and stayed to work as a city planner for many years.

I found it fascinating to use my reporting skills to elicit stories from thirty-five people with similar backgrounds yet very different immigrant experiences. I was delighted when the Library of Congress asked me to speak on this topic and requested the audio recordings and full-length transcripts for its collection, now available for future researchers.